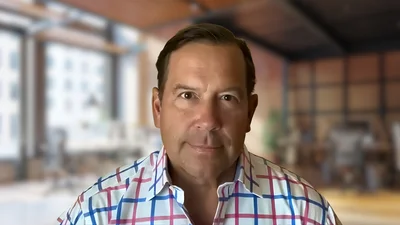

House Speaker Michael Madigan

House Speaker Michael Madigan

Illinoisans watched a new chapter of House Speaker Mike Madigan’s 50-year political drama unfold July 17.

Federal agents announced a record-breaking $200 million prosecution agreement with Commonwealth Edison for bribing the speaker, referred to in official documents as Public Official A. And soon after, authorities swarmed Madigan’s Springfield office, serving a grand jury subpoena for a wide range of documents.

Still, the state’s most prominent Democrats refused to call for his immediate resignation.

Gov. J.B. Pritzker, Cook County Board President Toni Preckwinkle and others used an “if true” qualifier before saying the speaker should step down.

With Madigan on the ropes like never before, they’re still afraid.

Madigan has held the speaker’s gavel for 35 of the last 37 years. Illinois’ median age is 37 years old. No legislative leader in American history has held power for longer.

How did this happen? And if his own party won’t hold him accountable, what can Illinoisans do to fight back?

First, they must understand Madigan’s unprecedented power comes from policy choices – not random chance. And they must understand which choices matter most.

His iron grip has five fingers: the rules, the party, the map, the law firm, and taxpayer-funded patronage.

The House rules passed by his caucus members every two years give Madigan more power than any other legislative leader in the nation. No bill will pass in Springfield, much less receive a vote or public debate, without his blessing.

Madigan is also the only state legislative leader in the U.S. who pulls double duty as the state party head. Since 1998, Madigan’s dual role as speaker and chairman of the Democratic Party of Illinois has given him direct control over both policy and politics. Trial lawyers, public sector unions, public utilities and other special interests trust their money will protect them in Springfield if it goes to Madigan. Vulnerable Democrats trust Madigan’s money will protect them on the campaign trail. And Madigan trusts those Democrats will protect his speakership. The system is near-perfect. They have elected him speaker 18 times.

Madigan controls the legislative map, meaning he has rewarded allies and punished enemies when drawing Illinois’ political boundaries for three of the past four decades. One result: About half of state lawmakers will run unopposed in 2020. While campaigning for governor, Pritzker promised an independent mapmaking process following the 2020 Census. The speaker is not interested. So Pritzker has walked back that promise, and refuses to endorse a popular, bipartisan constitutional amendment in the Illinois Senate that would establish independent maps.

Madigan founded his law firm, which specializes in the notoriously corrupt game of Cook County property tax appeals, in 1972. Madigan has never fully disclosed his sources of income but makes over $1 million “in a good year,” he said in 2015, because wealthy real estate owners feel pressure to throw business to the speaker. Every dollar Madigan’s firm saves its clients shows up on somebody else’s property tax bill.

Finally, that leaves patronage.

Madigan’s first real job was a patronage job. His father, a precinct captain for Chicago Mayor Richard J. Daley, got him work in the city's law department. One of the most important lessons Madigan learned from Daley was that building a patronage army was the key to longevity.

"I mean, everybody wanted to be a ward committeeman. They knew the power of the patronage system,” Madigan said in a 2009 interview, 40 years after he was elected 13th Ward committeeman. “They wanted a job in the patronage system ... I would tell them, ‘Yes, we can put you in a job. But you’re going to work for the Democratic Party.’”

Daley built his patronage machine with federal money. The speaker built his with state money, more specifically state debt. Political foot soldiers owe generous pensions, early retirements and other perks to the speaker’s protection.

One example: leaked emails show Madigan’s confidant Mike McClain fought to protect state worker Forrest Ashby from discipline, saying Ashby “kept his mouth shut” about “the rape in Champaign” and “Jones’ ghost employees.” Pritzker’s gubernatorial campaign later hired Ashby on McClain’s recommendation. Why would someone like Ashby keep his mouth shut to protect Madigan? Well, he retired at age 54 after contributing $120,000 toward his retirement over 29 years in state government. In return, he will receive an estimated $2.7 million in pension payments. This is the norm.

Most Illinoisans have never cast a vote for Madigan. A small district near Midway Airport sends him to Springfield every two years. Then House members make him speaker. He's kept power through the rules, the maps, the party, his law firm and patronage fueled by debt.

That's about to change.

After taking millions of dollars in donations from Pritzker – including $7 million just before Election Day in 2018 – Madigan decided to risk putting his power up for a statewide vote on Nov. 3, 2020.

The speaker passed an amendment to scrap a key constraint on his taxing power: Illinois’ flat income tax protection. Pritzker sells this as a “fair tax.” But polling shows about half of Illinoisans see it as a “blank check” for some of the behavior summarized here.

Scrapping the flat tax would open flood gates for an Illinois retirement tax, local income taxes and tax hikes on the middle class year after year. It's the most important ballot question Illinoisans have faced in 40 years. They don't come around often.

No one knows whether or when a federal indictment is coming for Madigan.

What Illinoisans do know is what his unprecedented political power has done to the state.

And in a little over three months, Illinoisans will decide whether they want the speaker to have more power or less.

– Austin Berg is a Chicago-based writer with the Illinois Policy Institute who wrote this column for The Center Square. Austin can be reached at aberg@illinoispolicy.org.

Alerts Sign-up

Alerts Sign-up